July 1, 2025

The Illegibility of Prices in Non-Competitive Markets

Why did Rockefeller get paid when his competitors shipped oil?

In the second half of the 19th century, John D. Rockefeller’s company, Standard Oil, negotiated some funky contractual terms with the railroads to ship their oil across the country. It’s not that weird that a big oil producer would get a good price on freight. The weird thing is that the railroads agreed to pay Standard Oil secret kickbacks on all shipments, even those for Standard Oil’s competitors. These payments could be big, typically amounting to 15% of the nominal freight price. When the public discovered these business practices, people became angry and confused. Why would the railroads agree to write checks, referred to as “drawbacks,” to Standard Oil on transactions to which Standard Oil was not a party?

The Justified Costs Theory. Standard Oil would later explain the payments as compensation for the savings they were conferring on the entire industry. First, since railroad costs are mostly fixed, by generating lots of stable volume, Standard Oil was reducing average unit costs for everyone. Second, Standard Oil was providing services to the other railroads, particularly warehousing, so it wasn’t weird for them to be paid for those services.

Many scholars see these arguments as dubious and believe they conceal the real motivation for the railroads agreeing to drawbacks. Standard Oil negotiated these terms before achieving majority market share, so it’s weird for them to get all the credit for economies of scale. That argument might get the causality backwards, where favorable freight pricing contributed to Standard Oil capturing most of the market. Moreover, if these kickbacks were payments for warehousing or other services, why weren’t they connected to provision of services, rather than calculated based on competitor freight sales? And why were they kept secret? And why were the kickbacks so much larger than fair market value for the services rendered?

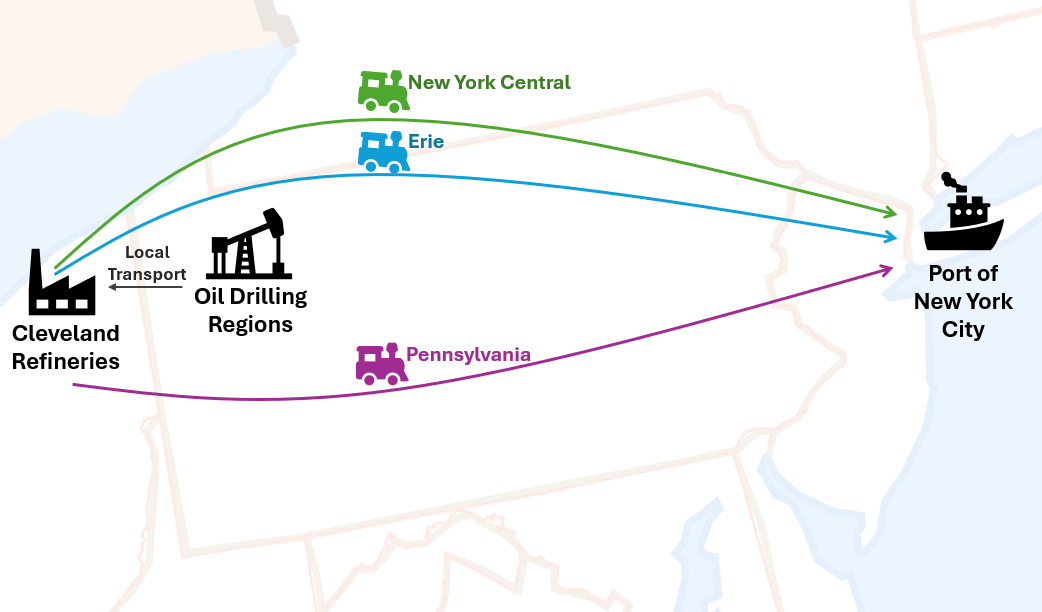

The Conspiracy Theory. The alternative theory is that the railroads paid Standard Oil kickbacks for railroad conspiracy services. In the 1870s, the typical supply chain was for oil to be drilled out of northwestern Pennsylvania, routed by local transport to midwestern refineries, and then shipped to east coast ports for international export. Railway freight was overwhelmingly provided by three railroads: Erie, New York Central, and Pennsylvania.

Both the capital-intensive nature of railway operation and the boom-and-bust oil market guaranteed that the railroads never quite had the right amount of capacity. Too little, and they’d miss out on the gold rush. Too much, and half-empty rail cars killed their ROI. They dreamed of a joyous cartel, where they could charge stable prices and jointly coordinate freight across their infrastructure. But cartels are hard. Anytime one of the railroads was not at full capacity, they could boost market share by cutting prices, causing crashing freight prices during oil busts.

To maintain a cartel, you must be able to punish defectors. Since Standard Oil had refineries in Cleveland, which was a major transport hub, they could quickly re-route their supplies through any of the three railroads. This made them uniquely positioned to play enforcer and ringleader for the railway cartel. Standard Oil would evenly divide their production across the railroads, and the railroads would charge coordinated prices. If any of them thought about defecting, Standard Oil could credibly threaten to ice them out by re-routing to their two competitors. Since Standard Oil’s role was to monitor compliance across all oil freight, they were paid fees even on their competitors’ shipments – hence the drawbacks.

The Occam’s Razor Theory. The conspiracy theory is widely-regarded and the originating paper has about 300 citations. But does it actually make any sense? Do the railroads really benefit from helping Standard Oil take over the entire refining industry? Wouldn’t that give Standard Oil a ton of bargaining power in future negotiations? It sounds a bit like feeding the beast that later devours you. Or perhaps Bostrom’s Unfinished Fable of the Sparrows. Only, in this case, the story is in fact finished, in that it happened 150 years ago, and the railroads did in fact lose most of their oil income once Standard Oil became big enough to build their own pipelines.

Maybe Standard Oil collected drawbacks because John D. Rockefeller and the railroads felt like doing it that way. The drawbacks were just the messy result of bilateral negotiations between a near-monopsony and an oligopoly. When you have a few big players with roughly balanced bargaining power, the deals they cut often look weird from the outside because they're optimizing for things that aren't obvious - like administrative simplicity, timing of payments, risk hedging, or operational flexibility. The railroads and Standard Oil were both large, sophisticated entities trying to lock in profitable long-term relationships. Maybe the drawback structure was just the particular way they chose to split the economic surplus, and all the elaborate theories about cartel enforcement or service compensation are overthinking a handshake deal.

Analogizing to health insurance. If you like opaque, seemingly irrational pricing arrangements in concentrated markets, you may also enjoy the U.S. healthcare system. The public gets upset by how weird healthcare prices for individual services look. But insurers and health systems aren’t actually haggling over each visit or even for each type of service. Instead, these negotiations are often based on simple benchmarks, where the insurer agrees to pay 50% over Medicare rates across broad categories of care. And then they also agree to a whole series of performance-based or volume-based bonuses that get calculated based on whole bundles of production, get adjudicated on a delay, and have to be subsequently adjusted and reconciled.

So money is flying back-and-forth, and it all makes perfect sense to the accounting departments within the big insurers and big integrated health systems. But then the regulators say “tell me how much the hospital was paid for this particular patient, and make sure you include all those crazy discounts that I don’t understand.” And the insurer is like, “well, it doesn’t really work that way.” And the regulator says “just do it!” And then the data looks weird, and people get very upset.

Then, people get all sorts of weird ideas about causality. Where they think that, because a price was calculated based on some benchmark, moving the benchmark will move the price, as if the parties involved were the sleepiest of robots. When in reality, the “price” was negotiated based on aggregate targets using historic claims data, and the benchmarks were just a convenient thing to point to.

Even after 150 years, researchers can’t agree on exactly what was going on with the Standard Oil drawbacks. And while it’s fun to speculate, we shouldn’t expect to really know. Because pricing in uncompetitive markets usually won’t be legible to outsiders.

o3 Fact check: Here’s a fact check of this post from o3 with my responses in red.