What Economists Get Wrong About AI

A recent OECD study both projects productivity gains from AI and also compares their findings to related literature. It's worth reading both as an effective explainer of how the economics profession is thinking about the issue and as definitive documentation of their confusion.

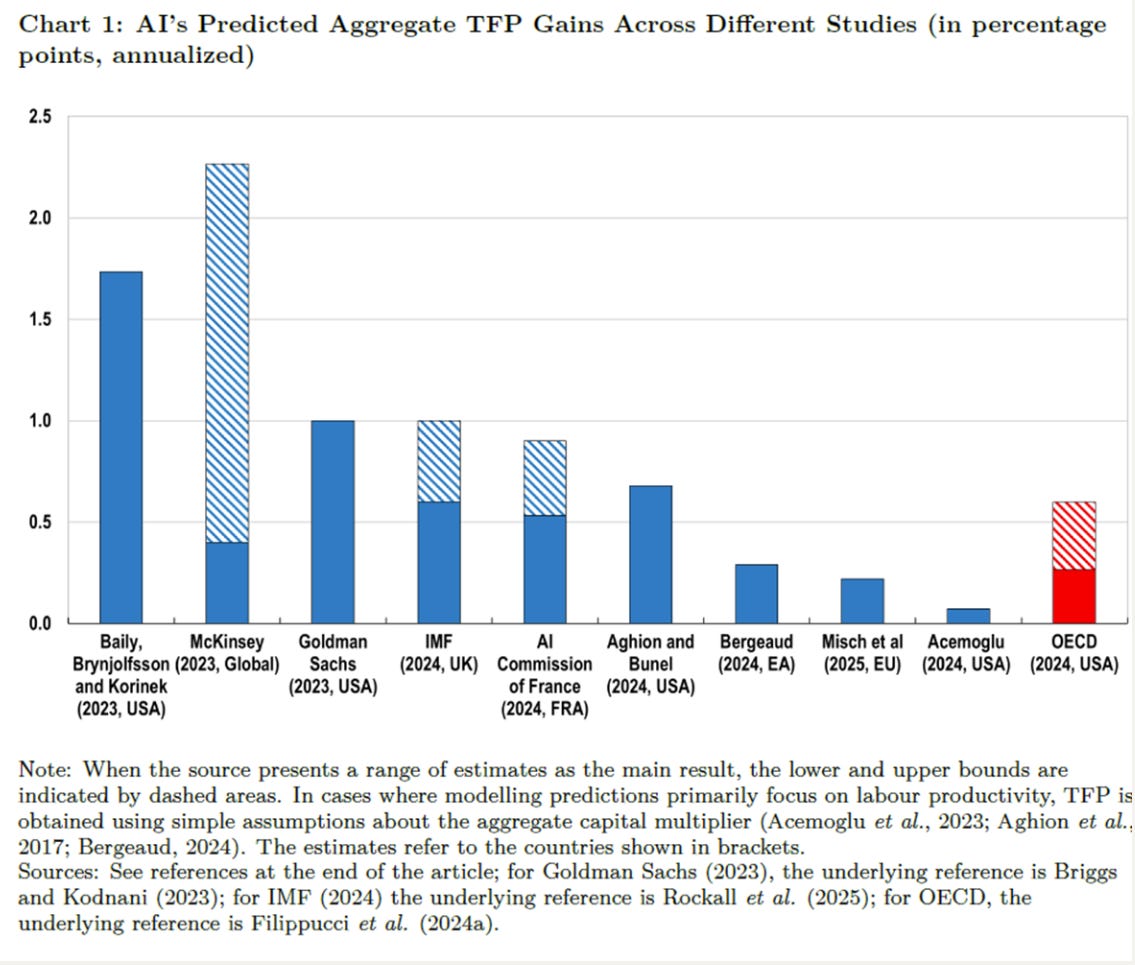

The authors estimate that AI will increase annual growth in GDP over the next decade by somewhere between 0.3pp and 0.7pp. This is roughly in the middle of the published literature, which mostly ranges between 0.2pp and 1.0pp. By comparison, information technology has been boosting productivity by somewhere between 1.0pp and 1.5pp since the mid-1990s. Most of the economics literature is telling us that in the near-term, AI will be less economically disruptive than the internet.

The OECD folks do a nice job of expressing their model as mostly the product of three assumptions:

AI exposure. The percentage of the economy exposed to productivity gains from AI.

Adoption rate. The rate at which exposed sectors will incorporate AI technology.

Effects on AI adopters. The extent AI will improve productivity within exposed sectors that adopt the technology.

For example, in their upper bound scenario, they assume:

50% of the economy will be exposed to AI;

40% of those sectors adopt AI technology by the end of the decade; and

30% productivity gains for those sectors that adopt.

That implies a 6% cumulative productivity gain by the end of the decade (50% x 40% x 30%), which translates to less than 1% of extra GDP growth per year. Their model is more complicated than that, but those assumptions drive the results.

First, let’s acknowledge how clearly this paper is written and thank the researchers for their great work. Second, let me explain why these estimates are too low.

Problem #1. They don't account for innovation effects

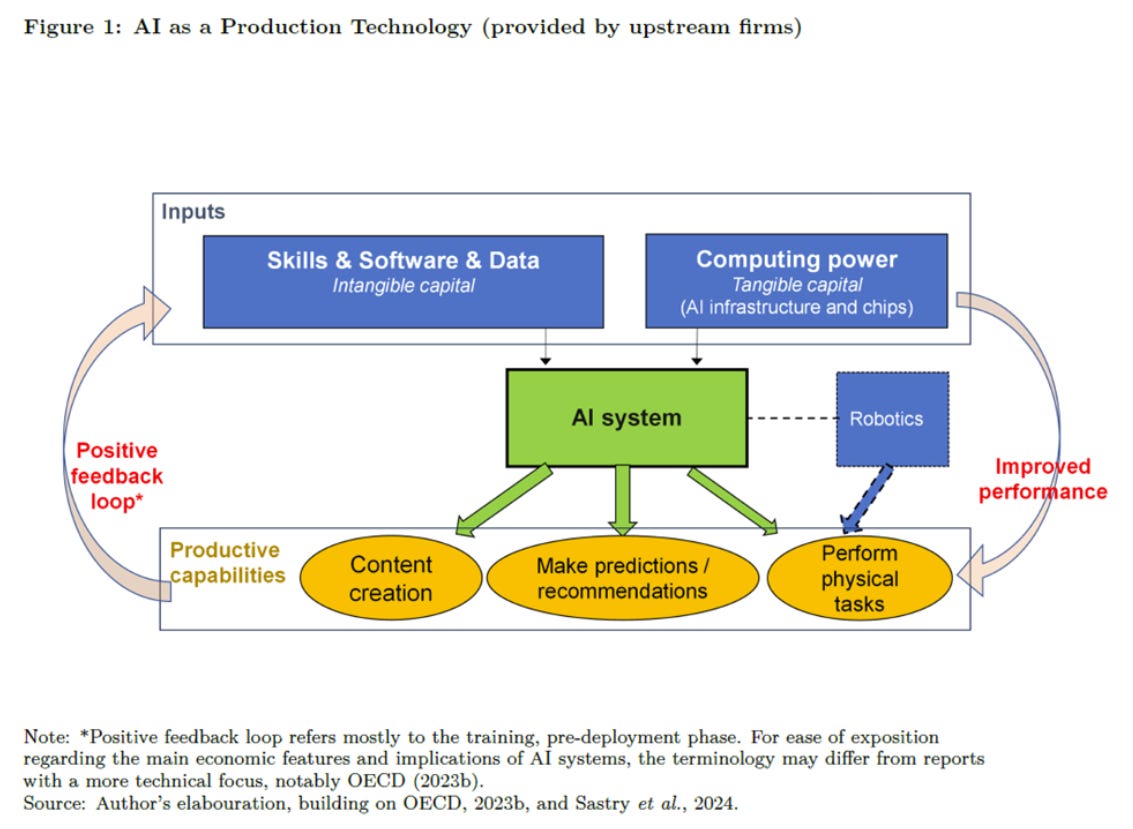

The classic story for how AI drives explosive growth involves a positive feedback loop, where AI accelerates innovation and that acceleration improves AI. The OECD researchers have clearly heard this story and even provide a chart.

Where do these innovation effects show up in their models? They are entirely omitted, both by the OECD researchers and by the other economics studies which they review in detail.

Again, the authors seem completely on-board with AI driving productivity gains through innovation, stating:

“There is empirical evidence of AI increasing the productivity of researchers and boosting innovation. Calvino et al. (2025b) review the existing literature and show that generative AI accelerates innovation in academia and the private sector.”

“If AI can increase the rate of technological progress, the productivity gains over the next decade could be larger than what we predicted. Aghion et al. (2017) and Trammell and Korinek (2023) discuss the possibility that such a scenario leads to explosive growth in the medium term, while also pointing to possible limiting factors, such as Baumol’s growth disease."

Basically, when you try to include innovation effects, the results get too weird and sensitive to speculative assumptions, so they ignore them and call it a “limitation.” But most people who cite these headline numbers will never read that part of the paper. They'll read these numbers as central estimates, when they should be read as lower bounds.

Problem #2. They have dated views on AI capabilities

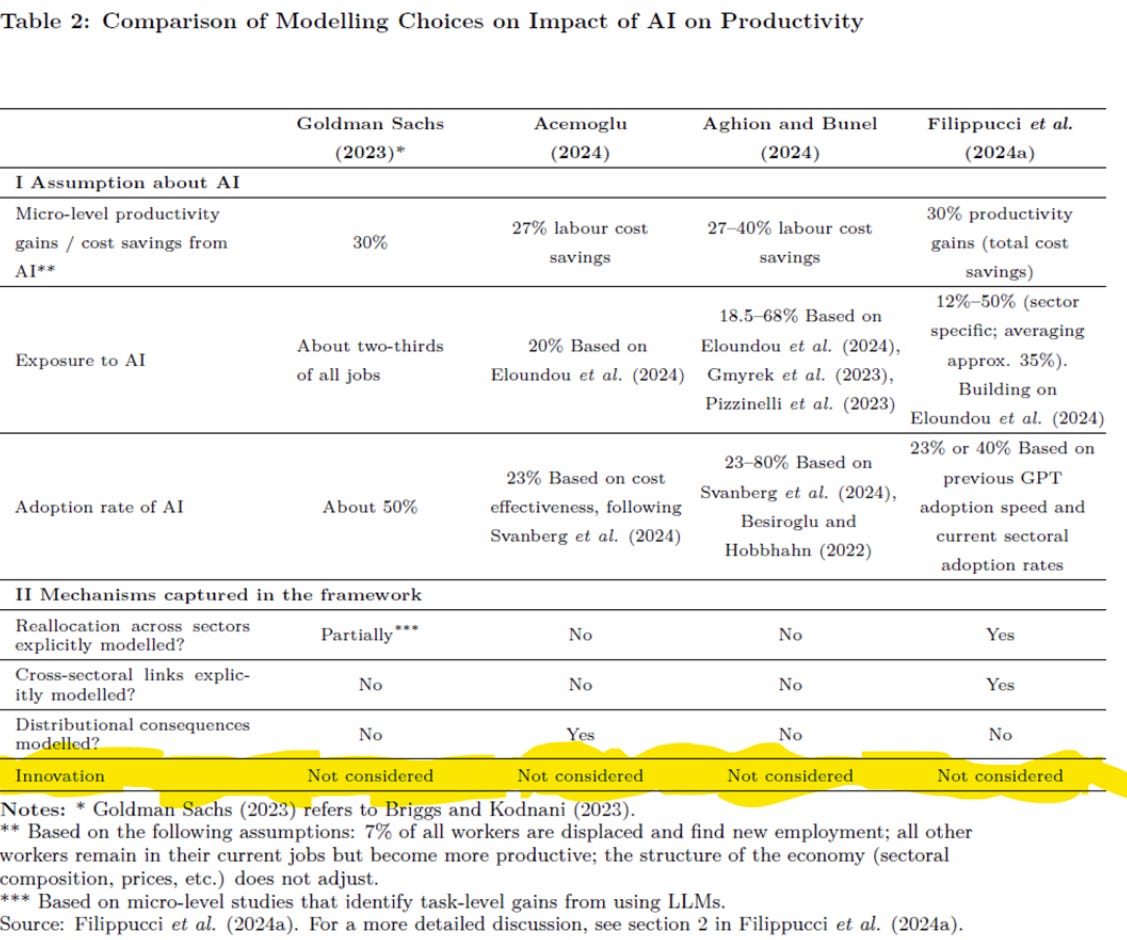

You would think the magnitude of AI's productivity effects for AI users would be a key variable driving differences across studies. And yet, this assumption isn't driving much of the variation in the literature. All four papers covered in detail by OECD assume somewhere between 27% and 40% productivity effects (see Table 2).

Once again, the OECD researchers are right in the middle of the literature, assuming a 30% productivity gain. Here is how they justify it:

Still, to remain conservative, we will assume a 30 percent micro-level gain, which is close to the average of the three most precise estimates and excludes studies on coding, where the productivity gains from AI may be particularly large.

Forgive me for a brief digression, but when I read the word "conservative," I think "lower bound." But when I read their abstract...

Drawing on OECD work and related studies, it synthesizes a range of estimates, suggesting that AI could raise annual total factor productivity (TFP) growth by around 0.3–0.7 percentage points in the United States over the next decade...

... I think "upper bound." That's not ideal, but things get worse.

Their 30% productivity gain is based on three studies:

Brynjolfsson 2025. Based on real-world data collected in 2020 and 2021, AI assistance is found to improve customer service call volume by 15%.

Dell'Acqua 2023. Based on experimental data collected in 2023, access to GPT-4 is found to improve the performance of management consultants on work tasks by roughly 40%.

Haslberger 2025. Based on experimental data collected in 2023, use of ChatGPT is found to increase the writing speed of emails and responses to written questions by roughly 50%.

Take the average of these studies with a broken calculator and you get the OECD's 30%.

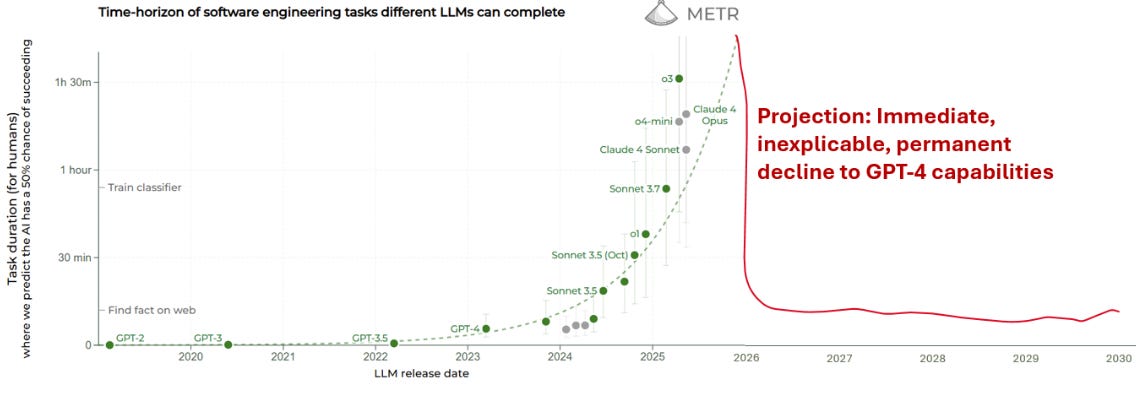

Given the recent trajectory of improvement in AI models, it's pretty bad to proxy the capabilities of 2025 models with data from 2023 and earlier. But what they're doing is even worse. They are proxying the capabilities of 2035 models with data from 2023 and earlier.

Remember that neat METR curve that was showing capabilities were doubling every 7-months? This is like assuming that, instead of the trend continuing or gradually leveling off, models immediately lose 90% of their current capabilities and then stay that bad forever.

Put briefly, the productivity studies are making very bad assumptions about productivity.

Problem #3. They don't appreciate robotics

Remember three years ago, when the cool demos for humanoid robots were pre-programmed gymnastic routines, which wasn't obviously economically useful.

And now the cool demos show humanoid robots manually sorting packages in real-world settings, which have obvious economic use cases.

That change happened because we invented robot brains that could be stuffed into the robot heads. They became better at understanding instructions, adapting to their environments, and planning. That makes the robots much more useful. Because cognitive and physical skills are synergistic.

These economists don't get this. For example, going back to Figure 1, notice how "Robotics" is omitted from the positive feedback loop. They are expecting robotics to be this big bottleneck. Instead, AI agents are about to dramatically improve the value proposition of robotics. This is going to fuel investment, which will lead production to scale and unit costs to fall.

Their blindness to these dynamics leads them to significantly under-estimate occupational exposure to AI. For occupational exposure, most of these studies are relying on Eloundou 2023. In that study, the authors went job-by-job and determined what share of tasks could be done by large language models. I underline large language models, because that is not the same thing as AI.

You can see this difference in the Eloundou graph showing AI exposure by occupation, which identifies sectors like "Truck Transportation" as having low AI exposure. But even if it would be hard to literally get ChatGPT to drive a truck, trucking is definitely on track to be automated by AI-based technologies in the foreseeable future.

To be fair, the OECD researchers arguably account for this some by considering a scenario where occupational exposure to AI is about 40% higher than what the Eloundou paper would imply. But they describe that scenario as accounting for general capability expansions, rather than accounting for limitations in the Eloundou-based estimate.

I feel bad for beating up on the OECD authors, because I am truly grateful for their methodological transparency. A lot of the limitations I'm flagging, both in their research and other published studies, jump right out of the report. And that's to their credit.

At the same time, I think their research and other studies from extremely respected economists vastly over-state their conclusions.

They say something like:

AI will increase productivity by less than 1% per year.

What they really show is:

GPT-4 will increase productivity by less than 1% per year, assuming it isn't helpful for innovation.

And those are completely different statements.